First off, here’s the link to our presentation:

In the first week, we formed teams and learned a lot about 3D scanning, archeological discovery and codes of conduct and ethics in these fields. I appreciated the lecturer’s input and the emphasis he put on how important it is to, when displaying an artefact, to try to provide as much context to the viewer as possible, in order to respect the piece.

For this project, I wanted to start with imagining different “experiences” we can find in museums. During the first week of the project, I visited the Kelvingrove museum and enjoyed its wide variety of pieces, as well as the expressive face sculptures in its centre. I then visited the Burrell collection, and felt very moved by some paintings and how they were described by specific communities, rather than school-taught curators, such as the landscapes described by the 50+ walk group of Pollock Park.

I also thought about the PHI center in Montreal for its immersiveness and how it incorporates new technological art with every exhibition, and how they advertise to different ages. As well as the science centre, I would love visiting as a kid. I feel like I especially enjoy engaging with art, when I feel like it reveals something hidden, or that I didn’t know, about human existence. It strikes a special chord within me when it communicates something otherworldly or somewhat spiritual.

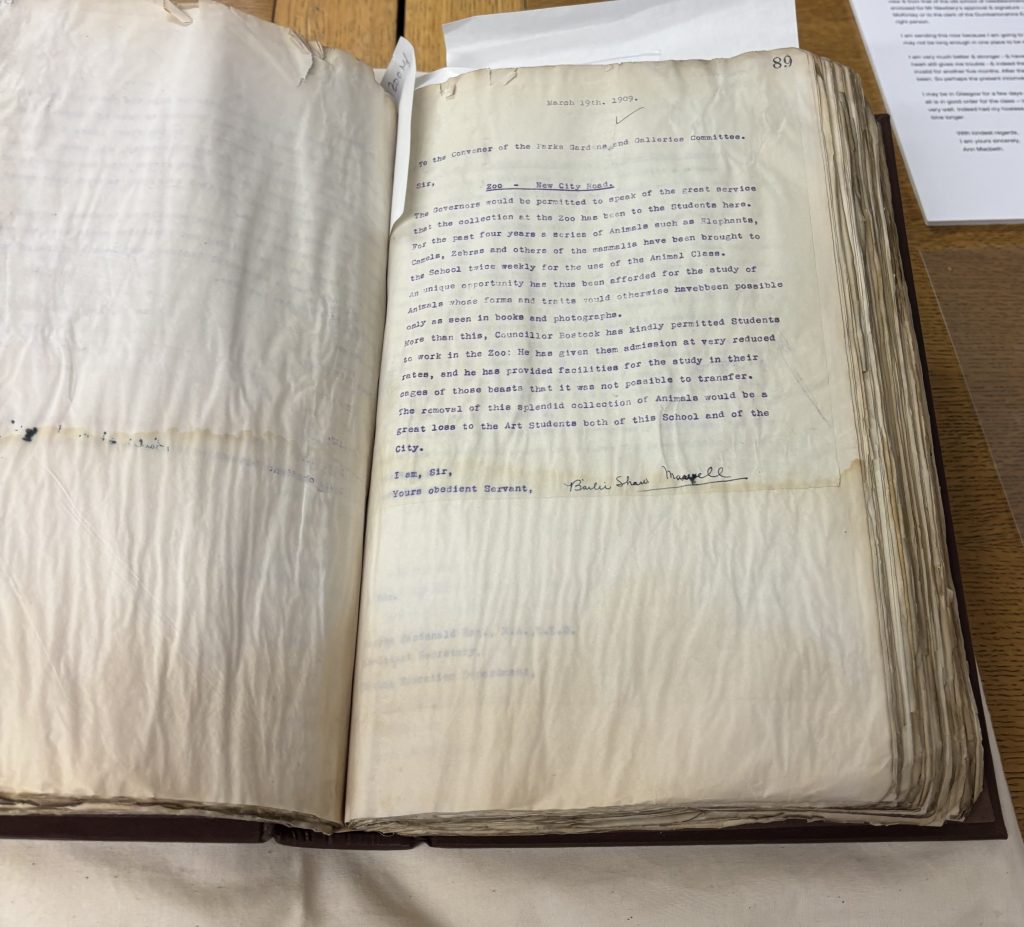

We visited the archive the following week, at the Whisky Bond, and I was impressed by the variety of artefacts I saw. I learned more about the Macintosh style, that I wasn’t particularly familiar with, as a foreign student. From what I remember, I saw the writings of some Glasgow Girls, tied to the suffragette movement, where a student in 1909 criticized the School of Art for having women as muses but not as students of the institution, by using a zoo as a metaphor. Here I was reminded of how art, even in its emancipatory nature and values, has and continues to display marginalized groups in order to fetishize them and not necessarily involve them in the debate. It was great to see how these items were preserved and the rich collection the school has, spanning several decades.

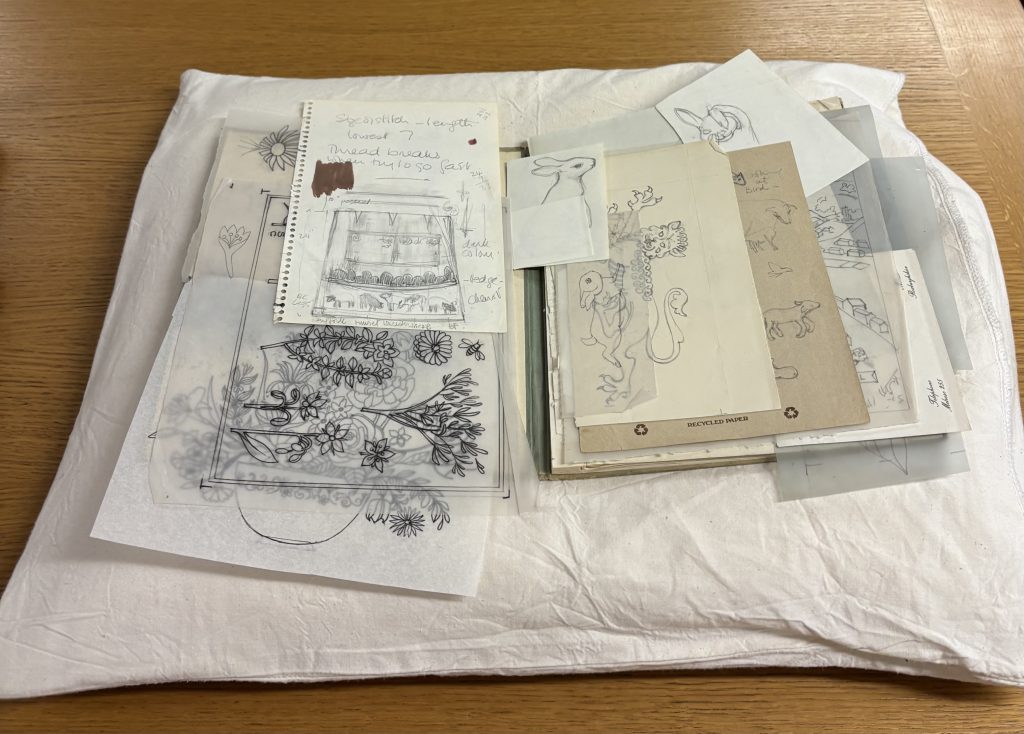

In teams, we discussed what interested us, we enjoyed some process sketches of some graphic design and drawing students. We also loved the jewellery items in drawers, presenting some original and fine pieces.

We then met a week later to choose an object we hadn’t seen at the archive, a Death Mask, made by Charles Smith, active from the late 1800s until the early 1900s.

We scanned it at the archive, using the polycam app, as well as taking pictures to eventually use photogrammetry.

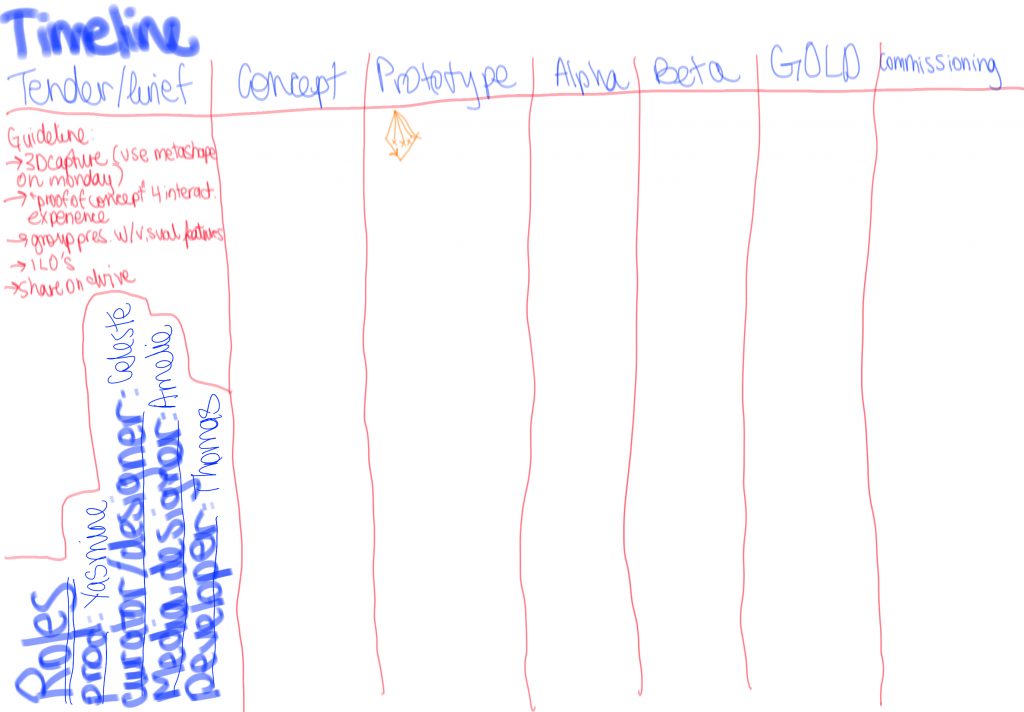

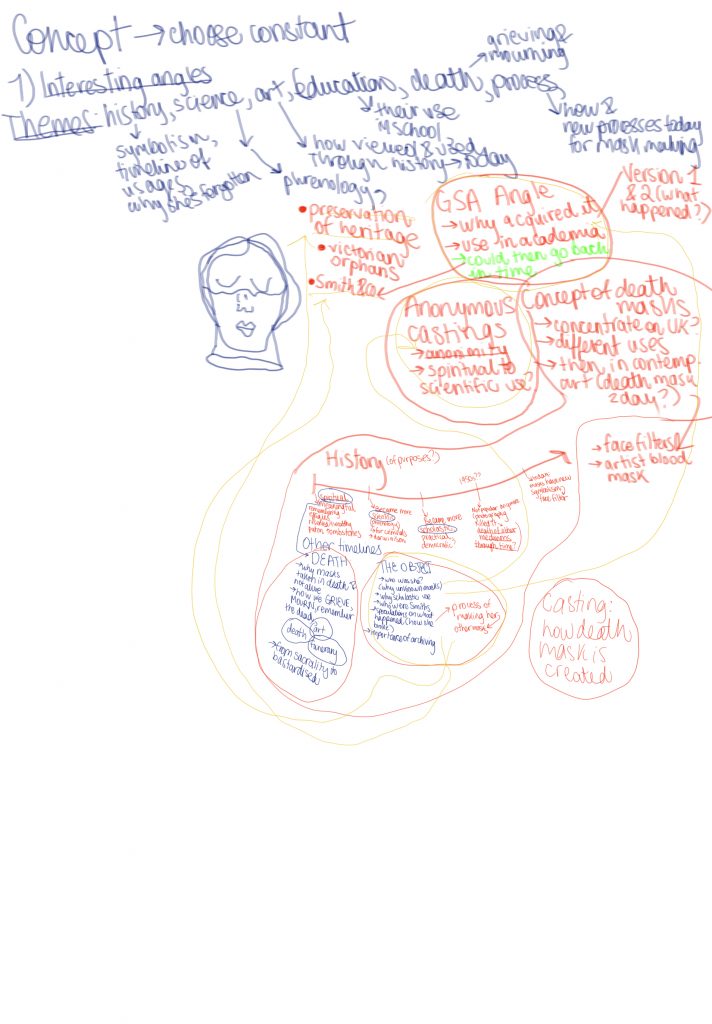

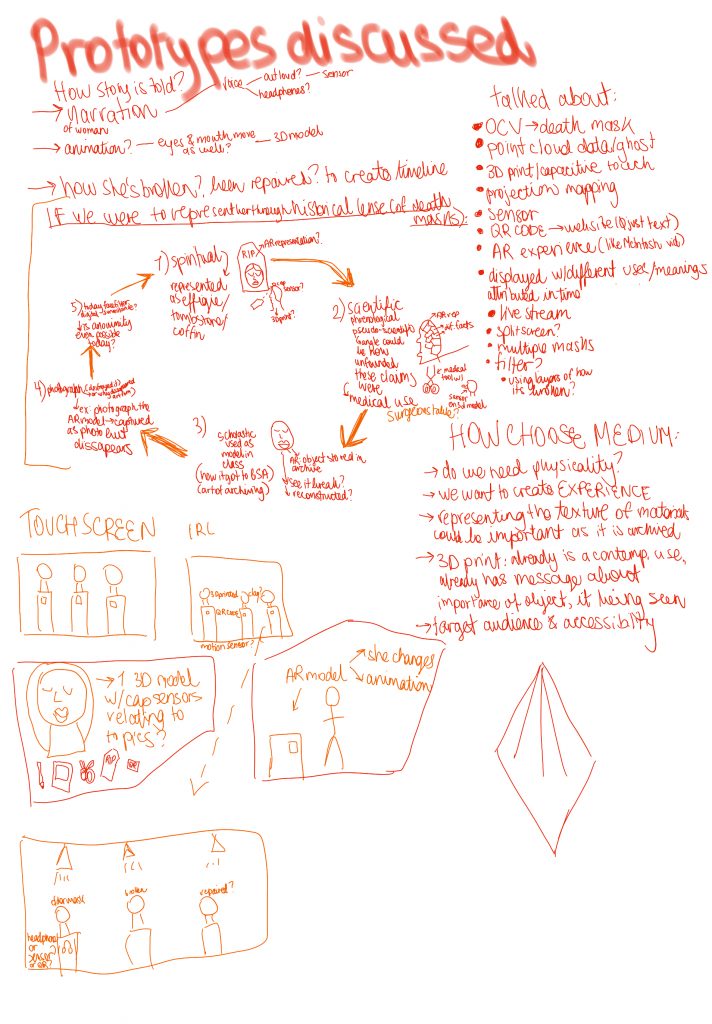

We decided to learn about the piece individually, and reconvene to talk about what interested us. Our first meetings were just dissecting the piece, and the history of the practice of making death masks. We were left with so many avenues of research, and weren’t sure where to go from there. We met with Pavel, the TA, to help us define what roles we should have. I chose to be involved with the production, as its something I enjoy doing, as a filmmaker who produces their own films, and as it could be easily delegated between the other students once I go back home. Celeste was to be the curator, as she is skilled in recognizing themes in art, and very conceptually sound, Amelie was to be the media designer, as she is great at representing ideas and themes visually, and Tom was to be the developer as he is fluent in code. After, we decided to brainstorm with these in mind, seing what themes were personally interested in, based on our research. We also discussed what mediums we could use to bring these ideas to life, crossing from our list ideas that were “unachievable” or that we weren’t interested in. We were narrowing down the key ideas and processes of our imagined installation, as well as thinking about our goals. Here are our key highlights from this:

-We wanted to make the experience accessible to a wide audience, therefore, a simple interface that doesn’t involve too much handling.

-We decided to determine the target audience later, if there was any.

-We we’re interested in the subject of death, of the temporary, memory and what masks mean to us today (Covid-19, surveillance, facial recognition, data).

I created a few representations, in order to remember what we talked about the following week. Here they are:

This lead us to focus on facial data more precisely, which connects the viewer from today to the 18th and 19th century death masks (just as the one we chose from the GSA archive), as opposed to the ones more commonly made in the previous centuries. We brainstormed again to decide what installation would work best, and as we all had things to work on (Celeste and I on how to explain these themes efficiently, Amelie on sketching the installation and deciding on what media we’ll need, and Tom prototyping our idea of “Hall of Masks” in processing).

After that, we reconvened, practiced the presentation, and determined what else should be said. Initially I thought of presenting our process similarly to the Learning Journal, but my teammates suggested I ease the client into why death masks are relevant today or in other words “making a comeback”. Also specifying accurately the timeline of their uses, in order to respect the archived item. Celeste made more links to known artworks, and researched data bases of facial data.

We then practiced all together another time, and we felt ready to present.

Here’s my text for the presentation:

“Here’s the Unindentified female death mask #2

Out of all objects in your collection, we decided to go with death mask as it has a rich history, that isn’t commonly known, and connections to contemporary themes, we thought we could create something immersive yet educational with this piece.

So we researched the history of the archived object in particular, and of the art of making death masks in the UK.

The mask comes from the Smith company, known for making death masks for educational purposes.

It was made by Charles Smith, a plaster figure and sculptor’s moulder in London active from the late 1800s until the early 1900s. After his death, his sons, continued the family business. The firm experienced financial difficulty in the 20s, although the family continued to be involved until 1953.

As you can see, the bottom is covered in a reddish brown shellac and the top half, appears to have been badly damaged, has been repaired with fresh plaster. This was the second version of the model.

We couldn’t find any information on who it was and so we were left to speculate on this anonymous face.

Here we can see the process of making a death mask, often made of wax or plaster.

If you’ve never heard of a death mask before, you probably know CPR Annie, which is the most widely used training manikin for teaching CPR and resuscitation skills. The fabricant was inspired by a popular death mask, the unknown woman of the Seine river (from the late 1880’s), based on a mould that he saw on the wall of his grandparents house. The unknown woman of the seine’s mould was taken because the morgue attender thought she was so beautiful and wanted a copy of her face. That lead to it being a mould many had in their cabinet of curiosities, such as the CPR doll’s fabricants grandparents.

Let’s talk about the forgotten art of death masks, making them, having them. I’ll be going over the key elements of our research.

First mask : Appeared a millennia ago, oldest example is Jericho’s head, discovered in the 1950s in Palestine. This mask was carefully moulded on the dead’s head as a way to remember him and to bring a community together around the memories of their ancestor . Death masks were created for this purpose for many decades, popular in antiquity and Ancient Rome.

Now if we look into the UK’s history, we know that in the Middle Ages, effigies were created for the nobles, but these were stylised and not realistic representations of the deceased.

In the Renaissance, the practice continued, and gained a bit of popularity, here we can see the death mask of Mary Queen of Scotts.

But it’s not till enlightenment and Victorian era that they became widespread. So we can notice a shift from their spiritual and funerary meaning to a more scientific and artistic one, as a memento mori.

They peaked in popularity in the 18th and 19th century, they were used by doctors, coinciding with a surge of interest in the pseudoscience of phrenology.

People would draw wild conclusions out of these masks of criminals, studying the skulls and the meanings of their shapes and measurements, categorizing their traits,.

We know that masks create a lot of engagement, as you may have heard of Madame Tussaud’s, which isn’t just a museum but a family of executioners that used to make masks from guillotined heads. She made life and death masks of the most infamous criminals of the day, such as Burke and Hare. 1830

So we can notice a certain democratization of these masks, as they went from being casted from known, nobles, to criminals, therefore unknowns.

It’s in this period that masks also became artist research tools, which is the case for the unidentified female death mask we chose. Casts had been used for centuries in academies of fine art and were now to be used as essential props for drawing based design courses. We know that it’s around 1830 in Britain, that the schools started importing plaster sculptures, for this purpose. Although, the art of making death masks gradually disappeared with the invention and democratisation of photography, another way of recording facial data, in life, or death.

“We all die twice – once when we actually die and once when no one on earth recognizes our photograph.” – Christian Boltanski

I’ve included this quote from artist, that works with themes of sacrality and remembrance, because I found it to be a beautiful metaphor for the death of death masks as a medium, as, it has, in sorts, been killed by photography. Now Celeste will explain the curation of this exhibition.”

Here’s a link to our Padlet, where we documented our research process more elaborately:

https://padlet.com/thomas_riddell52/experience-design-1ag4rodbc7kj50gx